The Poussin Collection

~

In 2012, the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, commissioned me to re-create a method Nicolas Poussin used to make the initial composition for some of his paintings. This work, was specifically related to the painting of one of Poussin’s masterpieces, “Extreme Unction” (1642), for their exhibition 'Silent Partners'. This marked the beginning of a series of wonderfully curious projects, a journey of re-discovery, and a uniquely collaborative, liminal dance between myself, the master, and his works.

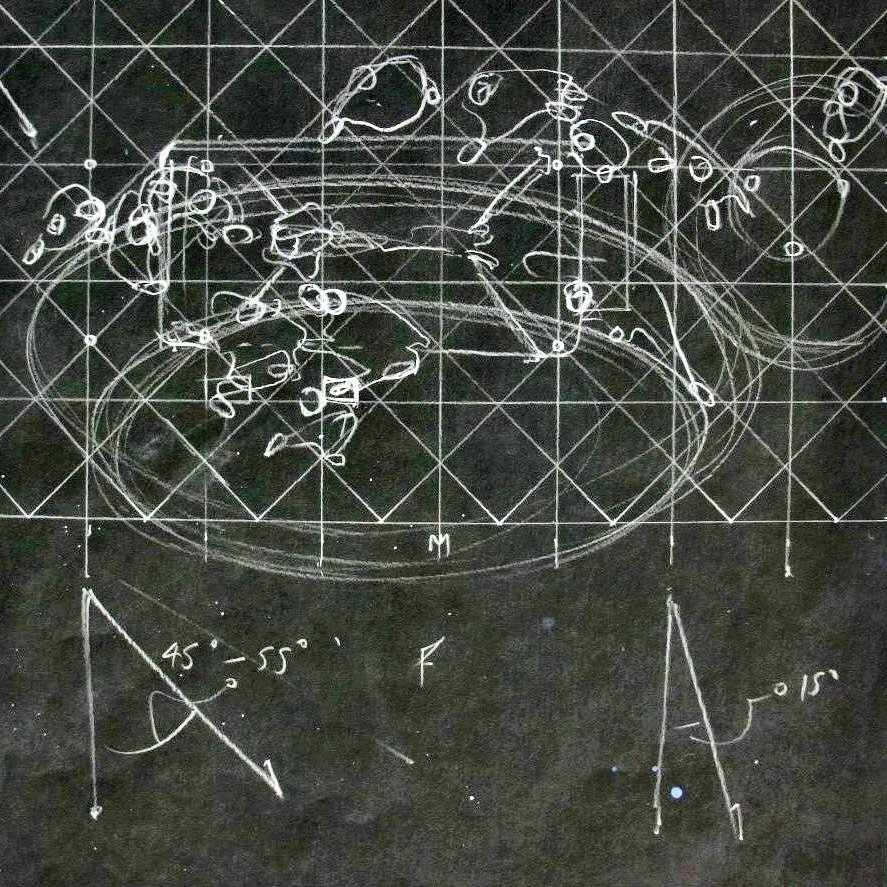

The foray into the world of Poussin starts with his great machine, an ingenious device used to set the stage for his compositions. The use of this device was journaled during his later period through his biographical writings and notation by studio visitors, providing a precious view into a famously solitary professional’s process. It was from these firsthand observations that the ingenuity of such a device could be re-discovered and ultimately re-constructed.

Le Grande Machine

This device illustrates how Poussin would have used a wooden box, known as the 'Grande Machine', to create experimental three-dimensional compositions to paint from. The machine resembled a 'scaled-down theatre', which he used to control the direction of light and background settings of the scene, such as temples, woodlands, and domestic interiors.

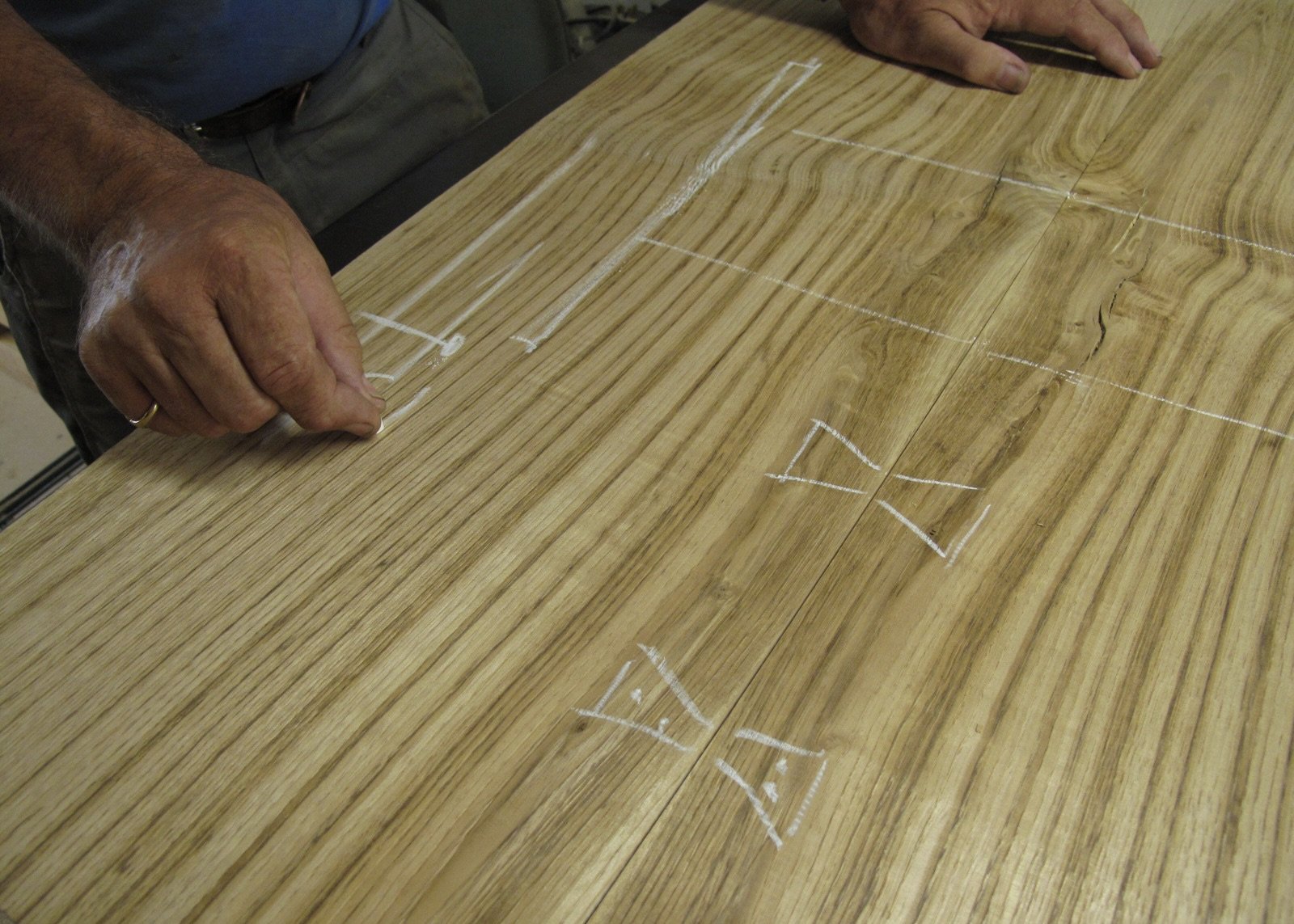

In order to manifest our very own Grande Machine, I studied Poussin’s preliminary sketches and contemporaneous descriptions of his works, particularly his Sacraments series, of which several excellent early drawings still exist. In collaboration with cabinet maker Robin Williams, Poussin’s theatre has been reinvented in sweet chestnut and now resides in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

The ingenuity of the invention became immediately apparent.

In many of the latter scenes of his Seven Sacraments, we can observe the ornate tiled floor designs which emulates the grid-referenced system utilised within the Grande Machine’s staging. In certain instances, such as in 'Extreme Unction', the fore-stage is clearly visible. This brilliantly efficient design not only aids in the positioning of the subjects but allows one to simply remove the entire stage and ensemble, set it aside for later, and recompose the scene.

A studious observer of light and its interaction with the natural world, Poussin respected this principle profoundly in the design of the machine. Two gated apertures along the side panelling of the construction allow for the perfect provision of luminance to the stage.

Poussin would have harnessed this device, capturing the organic quality of light amongst the scene set within its chamber, granting effortless freedom to choreograph his mastery of textures: wood, wax, cloth, silk, and flesh.

Extreme Unction

Poussin offers a dedication to the Seven Sacraments of the Catholic Church, a series commissioned in Rome circa 1637-1641. This particularly transcendent scene considers the rite of healing observed by the Catholic faith. In Extreme Unction, Poussin presents a classical scene of a Roman soldier on his deathbed. He is tended to by mother and daughter while receiving his ‘final anointing’ from a priest, assisted by acolytes who surround the scene.

There is a deep appreciation of the tonal qualities of the materials. Light raking in from the aperture to the left of our scene highlights the richness of colour in the subjects’ garments. This is countered by the green tonal qualities of the folds of cloth in shadow, which are equally reflected in the soldier’s drained flesh. One of the most reverential qualities that our recreation was able to emulate was that same brilliant luminescence captured amidst the scene from the reflection off the stage. In some way, the sanctum created within the box held some semblance of the ethereal nature that can be felt through the canvas.

The elegance of the process lies not only in the design of the grande machine itself but also in the materials of the figures and the sculptural aptitude of the artist. Subjects can be replaced, repositioned, and their garments changed seamlessly—a process that quickly became instinctual during the installation of the piece.

An artefact of this fluid nature is wonderfully preserved within the original artwork, as revealed by an analysis of the painting by the Hamilton-Kerr Institute of the Fitzwilliam Museum. Infra-red imaging exposes the incredibly intricate layering of the piece: from the initial illustration and ink shading to the complete corporeal figures beneath their elaborate garments.

Each figure in the reconstruction of Extreme Unction was sculpted from a blend of beeswax and pine tar which, once moulded and set, creates a suitably robust form. This is a poignant medium to work with, one that is historically analogous and infinitely mutable, softening with the heat of a small flame or the warmth of one’s palm. It’s this organic quality of the material that is essential in translating the flowing thoughts that Poussin speaks about in his application to his work.

Wax & Silk

‘Andrew Lacey in collaboration with Sian Lewis’

Poussin creates a composition on the grand machine using wax figures. But it's the coloured sequences of the drapes that guide the eye through the entire dance. The silks play a critical role in the overall composition, offering a floating choreography for the painting to follow.

Each silk also carries its own dynamic and symbolic meaning, helping the viewer uncover the subtler intentions hidden within the scene. To achieve this, tiny fragments of silk are pleated, pressed, dipped in water, and stretched over the waxen bodies until they mould perfectly to the form. Once shaped, they're hung-suspended in mid-air-completing their shapes and their delicate aerial dance that enchants the eye.

Triumph of Pan

Poussin’s work was contemporaneously celebrated for the revival of ancient traditions, classical techniques, and his sculptural and structural proficiency. His reputation has long been revered, serving as a profound inspiration for the Neoclassical movement. Contemporarily, his appreciation of form and structure reflected in his works can indeed be interpreted as both austere and scholarly.

In 2021, the National Gallery featured a series of Poussin’s works as the focus of their autumn exhibition, organised in collaboration with the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

‘Poussin and the Dance’ showcases a collection of works from his early Roman period, typified by bacchanal scenes. These works are wonderfully free, vibrant, intemperate, and, on occasion, decidedly hedonistic.

‘The Triumph of Pan’ is the first of a pair of displays I devised for the exhibition; a re-imagining of the namesake piece commissioned in 1636.

There is a surreptitiousness to this work—an unveiling of a spectacle we are now all privy to. Drawing closer, a chorus of pipes, horns, and cheers brings you into the fold, an invitation to a harvest festival, a cause for celebration, and an instance of tribute. Before us stands Pan, centre stage, orchestrating an evening of excess and mischief. Our characters, enveloped in the merriment to the fore, are set against a backdrop of a forest at dusk.

Whilst fervour and frivolity abound, the scene is rich with textural intricacies, constituting an immensely complex composition—one which is deeply infused with elements of the ancient world, including a frieze-styled arrangement, antiquities, and classical physiques.

In recreating the portrayal, there is a distinct parity between the re-modelled figures, inked sketches, and the canvas itself. The reenactment finds its place in the natural order between the preliminary charcoal work and the final piece, becoming a translator of sculptural physicality that embodies the figures throughout the scene.

Sabines

The final works of Poussin’s series of dances are a pair of paintings: The Abduction of the Sabine Women and The Dance to the Music of Time. Poussin offers a classical depiction of the infamous kidnapping of the daughters of the Sabine people, an event pivotal to securing Rome’s future and destiny. In The Dance to the Music of Time, there is a sense of resolution, hope, and healing. Hand-in-hand with one’s neighbour, there is unity and an enduring cyclicality to the human experience.

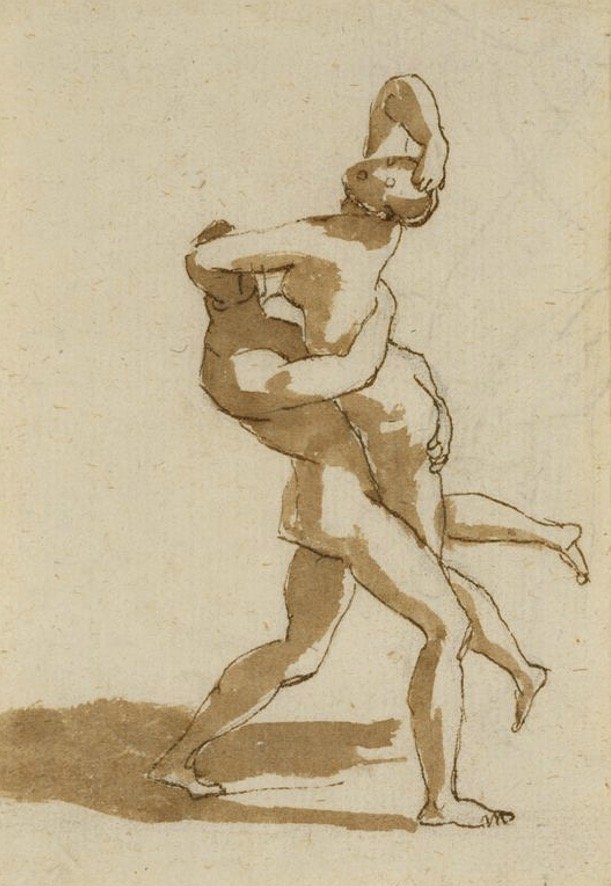

Among the selection of Poussin’s paintings featured in the National Gallery exhibition are several of his line and wash illustrations. These preparatory designs are beautifully rendered in charcoal and brown ink. It’s a joyous reunification.

They are spare and masterfully succinct.

In accompaniment to the illustration of The Abduction of the Sabine Women, a sculptural incarnation of this dance was created. The piece was subsequently cast in bronze after the exhibition and donated to the Royal Collection, Windsor.

The sculpture captures a dramatic and dynamic scene, a tense interplay between the man and the woman he is abducting. Their intertwined forms convey both aggression and an unexpected grace, a contradictory ballet of struggle and reluctant submission. There is an emotive fluidity in their movements, an intimate and combative embrace that mirrors the symbiotic tension of a dance—balletic yet fraught with conflict. The woman’s body, though forcefully taken, conforms to the man’s hold, tenderly capturing the intensity and complexity of this moment. This dance, transmuted into sculpture, reflects the natural relenting of the figures into their forms, resonating with the wax’s own effortless transformation into the final piece.